Japan – A visit to the Senso-ji temple in Tokyo

If there was only one place to visit in Tokyo, it would of course be Senso-ji temple. The oldest temple in the Japanese capital is a treat for the senses: the smell of incense, the sound of prayers, the magnificent decorations. Everything is there for a guaranteed change of scenery.

T

he streets are almost empty. The district looks more like a small town, quiet and pleasant, far from the agitation of the big districts of the Japanese capital. At the corner of a street, an elderly person quietly sweeps the front of his small shop with a supple gesture that betrays his advanced age. At the end of another, a cyclist crosses the alley peacefully. As usual, we are lost. Pungent incense fumes carried by the wind reach us. Senso-ji, Tokyo’s most famous temple – located in the Asakusa district and which we are looking for, can’t be far away.

Finding a place on the first try in Tokyo is more a matter of luck than anything else. As luck would have it, getting lost in the maze of concrete and glass also allows you to discover some unexpected places: traditional shops, temples, local markets. However, apart from a handful of bicycles and small shops, this area must be one of the most common in Tokyo. After about ten minutes of strolling, we decide to follow one of the few passers-by we meet in the street. The further we go, the more the smell of incense becomes present. At the end of a narrow alley, we leave the small town and land directly in the middle of a shopping mall, which seems to be very popular, considering the number of people there. Cosmopolitan Tokyo is never far away. Cafes, restaurants, small shops and souvenir shops have suddenly multiplied. Asakusa Shin Nakamise street – the name of the gallery – runs for more than two hundred metres and is completely covered, much to the delight of Tokyoites, especially during heavy rain or hot weather. If you need to buy souvenirs, Asakusa Shin Nakamise street is the place to go, full of handicrafts and Japanese oddities.

The excitement in the Senso-ji temple

As we arrive at the crossroads, the smell of incense has become omnipresent. In the distance, the low sound of a gong can be heard. The Senso-ji temple is only a few steps away. To the left and to the right of Asakusa Shin Nakamise street we discover a splendid alley decorated with tree branches in the colours of autumn. On one side of the street, it runs up to the famous Kaminarimon, the “Thunder Gate” and its gigantic four-metre high lantern, weighing more than six hundred kilograms. On the other side of the crossing, small souvenir shops and artisanal sweet and savoury delicacies rub shoulders all the way to the Hozomon, the door to the treasure room, symbolising the entrance to the Senso-ji temple and from which the smoke of incense and an indescribable hubbub emanate. We must not have been that far from the temple after all.

The Senso-ji temple is one of the most popular attractions in Tokyo. On this beautiful October day, the sunshine and mild heat attract young and old to the temple. Today’s Japan seems to be pulled in two completely different directions: that of modernity, progress, technology and a secularised society. On the other hand, culture, religion, animistic beliefs and old-fashioned customs are much more present than in Europe. However, these two aspects of society are not a dichotomy, and are very often complementary in contemporary Japanese society. One aspect of this can be found in temples such as Senso-ji in Asakusa. The crowding of the temple by Japanese people, the prayers and offerings, or the renewed interest of the young population in kimonos are just some examples. Few ethnic groups in Europe have managed to maintain their “identity” in the face of today’s uniformity, except for the Bavarians in Germany, for example.

The difficult question of religion

For us Westerners, such ‘religious fervour’ in the world’s third largest economy may come as a surprise. Or what could be called “religious fervour”. Even if Shintoism and Buddhism seem to be in the majority in Japan, the question of religions is a complicated one and is not limited to these two religions. For, as the CNRS researcher Jean-Pierre Berthon* says: “[…] the Japanese are unable to answer the most basic of religious questions: “What religion do you belong to? ” “. Above all, religion in Japan is practiced on a daily basis. Daily offerings in Kamidana and Butsudan – hotels of Shinto and Buddhist origins, visits to temples during special events (death festivals, new year) or during different stages of life (marriage, exams, new job). The issue of religion was also used for political purposes. As during the Meiji Restoration in 1868, when Shintoism became a state religion.

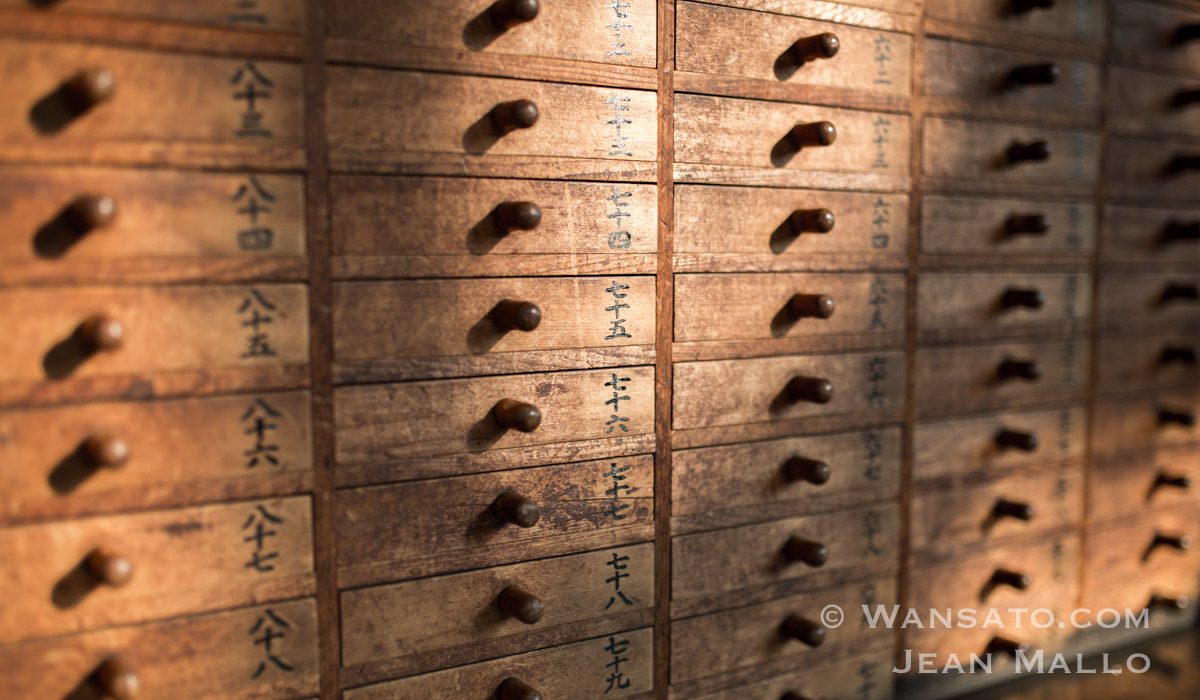

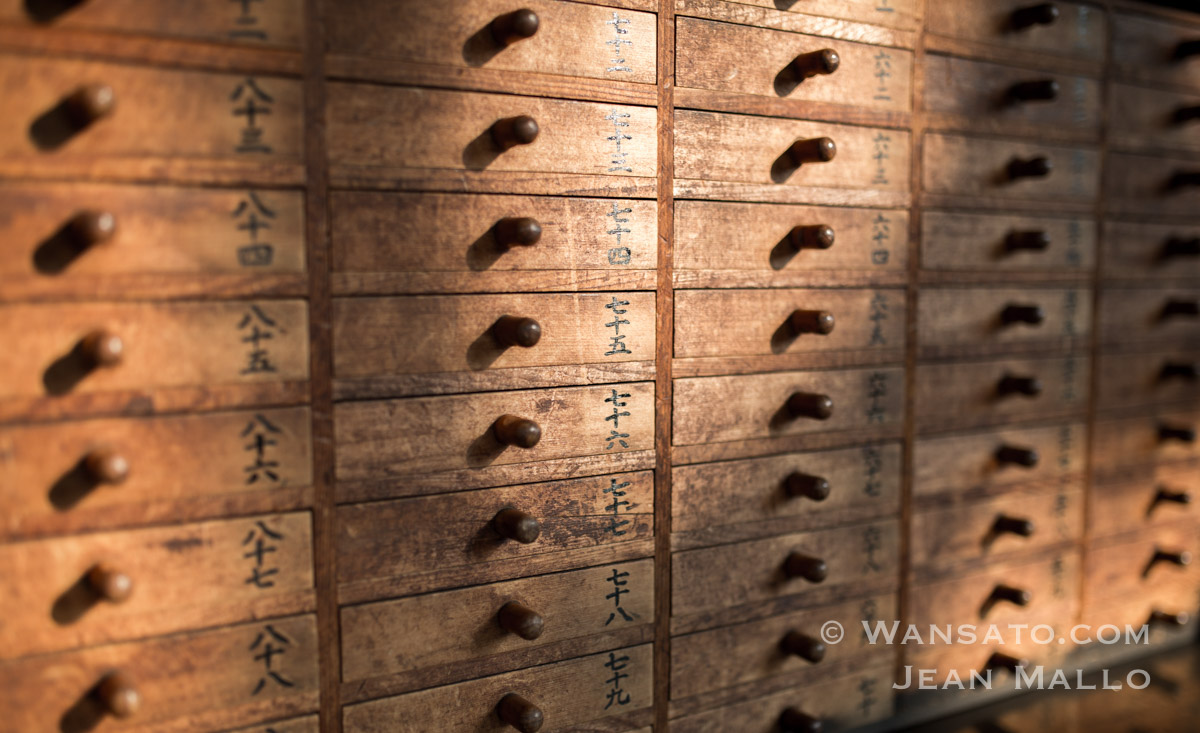

As for the Meiji-Jingū temple in Tokyo, there is a small fountain at the entrance of the Senso-ji temple used during the purification ritual. For tourists, this is more folklore, while for the Japanese it means being able to use the hands and mouth during prayers in the temple. The Senso-ji temple being a Buddhist temple, there is an incense burner in the centre of the temple, the smoke of which has therapeutic properties. It is generally said that the smoke comes directly from the gods, so people do not hesitate to burn a lot of incense and draw the smoke towards them with a gesture of both hands.

We let ourselves be overwhelmed by the spirituality of the place. As the sun begins to sink timidly, the light gives Senso-ji temple a special atmosphere. Add to this the prayers, the muffled sound of the gongs, the incense invading the interior of the Hondo – the main building, we let ourselves be taken in and greet the three local deities of the temple. It is already time to leave, the mando neri-kuyo festival is waiting for us at the other end of the city. On the way, we write on an ema – a small wooden plate – a message to bring us luck in life and all happiness to our loved ones. Something that seems to work quite well so far.

This Post Has 0 Comments